Welcome to La Miccia! This letter is too long to fit in your inbox. Head over to the website or click on “view in browser” to catch the full version. Thanks for reading!

I’m being told it’s very hot in NYC. I wouldn’t know because I’m in Montreal for the month and the temperature is clocking in at a cool 23°C.

However, if you happen to be in the city and need an escape from the heat, the museum (with its blasting AC) is always your friend.

And if you need some help picking out where to cool off for a couple of hours, may I suggest the Sargent & Paris exhibit at the MET? It’s on through August 3rd.

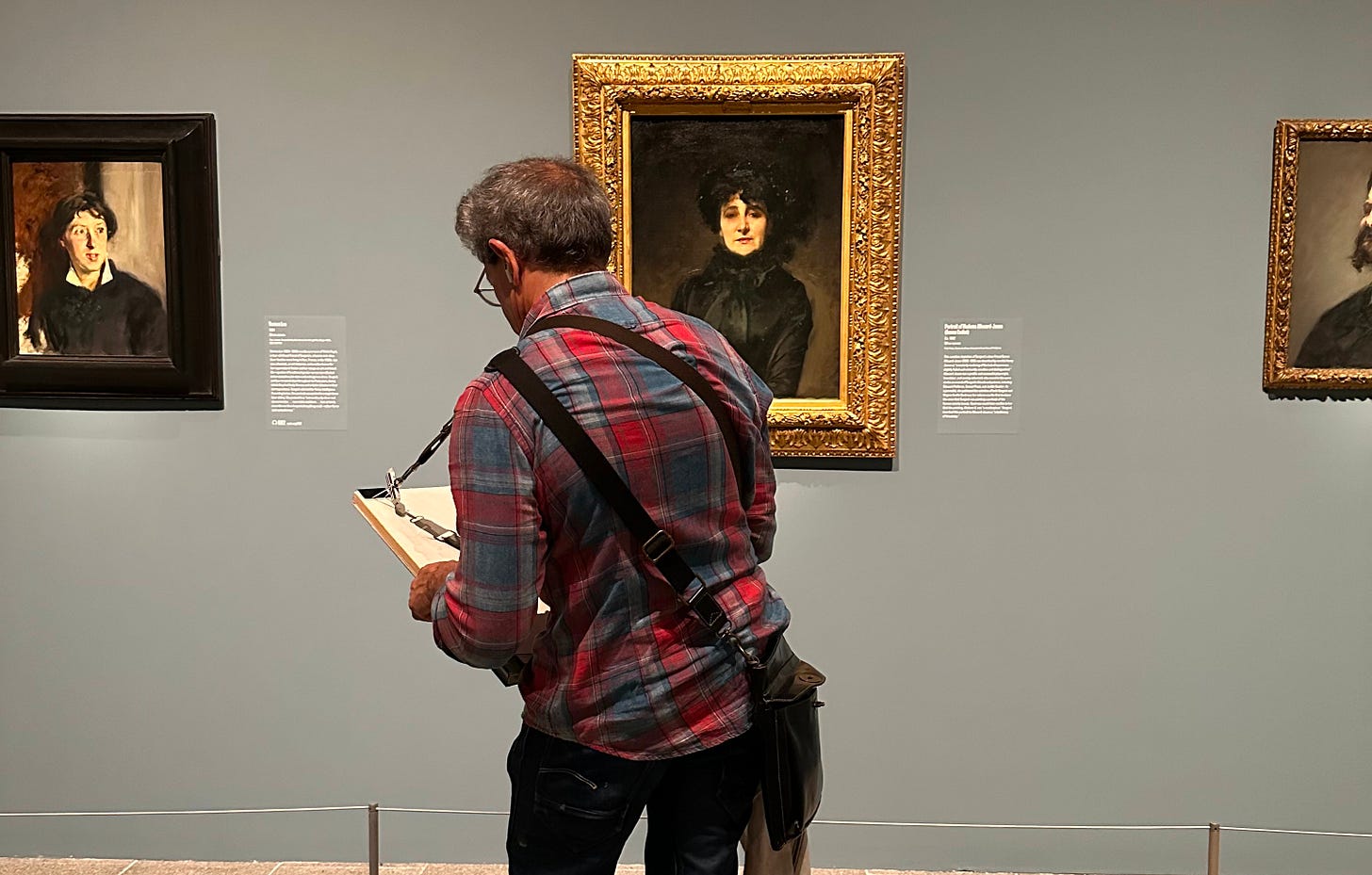

I took myself on a solo date to see this exhibition a couple of weeks ago, wandering in not knowing much about Sargent or 1800s portraiture, and was surprised by how much I enjoyed it.

On a purely aesthetic level, Sargent is a masterful figure painter who captures his subjects’ most striking and defining expressions. His rendition of fabric and clothing is particularly delicious: long, full gowns, draped skirts, fur scarves, feathers, and bows. His early work encapsulates the sultriness of the Gilded Age in France.

On a semantic level, I was struck by his search for unconventionality and his desire to paint people from all different walks of life. If I had to pick a word to describe Sargent (especially in his early years) it would be ‘curious’ - his work reflects an innate curiosity in exploring (and subsequently showcasing) all different facets of society, his attention spanning equally across elite families, dancers, priests, and doctors.

I love that he loved to paint his friends. I love thinking about all these people going about their daily lives, and I love that Sargent took the time to immortalize them.

It’s interesting to think about the people posing for him, standing still for hours on end. I like to fantasize about who had the most patience, and who would be agitated and restless. I think this as I walk through the gallery rooms. I think about the conversation before Sargent picks up the paintbrush, before he even sets up the easel - the conversation where the sitter and the painter agree on a pose, a location, an outfit (Sargent famously liked to pick out his sitters’ outfits).

I think about what their personality was like. How different were personalities in the 1800s from those of today? I’ve always thought it was an abyss, but some of the people I encountered during my wandering changed my perspective on that. ‘Edgy’ and ‘rebellious’ people existed back then too, as it turns out.

I like it when an exhibition makes me think about all these things. I like it when it makes me think about people and humanity.

Below, I share with you the paintings, or rather, people that stood out to me.

1. Rosina Ferrara

Early on in the exhibition, there’s a painting titled A Capriote from 1878. In it, a girl is wearing a flowy pink skirt, a white blouse, and a black vest. She stands with her back leaning on the horizontal branch of an olive tree. She is surrounded by an abundance of nature: grass and flowers sprout from the earth, trees occupy the foreground, with light glimmering, peeking out. Only one piece of the sky is visible, in the upper right corner.

Her sleeves are rolled up and her hair pulled back: the air must be hot and sticky. I can picture the sweat on the back of her neck. My skin itches thinking about the mosquitoes that are surely buzzing around. It’s summer, and the cicadas are singing.

She isn’t looking at us and seems absorbed in thought, as if she doesn’t know she’s being painted - as if Sargent just happened to stumble upon her while on a walk.

Right next to this painting is a portrait of that same girl. Her name is Rosina Ferrara. Looking at her up close, I can see that she is a young girl, and the label next to the canvas tells me that she was born in 1861 (which would have made her 17 at the time of painting). This portrait, titled Rosina Ferrara: Head of a Capri Girl, features a dedication to ‘Hyde’ in the bottom right corner.

In 1878, when Sargent was 22, he visited the Italian island of Capri. When he got there, the gallery wall text for Head of a Capri Girl tells me, he was looking for “a certain type” (meaning, with a nonwhite ‘look’) of model to paint. His interest in painting someone nonwhite, the wall text continues, was in “the artist’s pursuit of surroundings and exploits that took him beyond the white experience with which he himself, his portrait clientele, and his public identified.” To this end, his friend and painter Frank Hyde introduced him to Rosina Ferrara, whom Sargent ended up painting multiple times during his time in Capri, and allegedly having a romance with.

I kept thinking about Ferrara as I continued making my way through the exhibition. A muse fetishized for her features, at a time when such fetishization was under the guise of an artistic pursuit. I thought about her safety, about what her life was like after the summer of 1878.

We know how Sargent’s life went after their encounter - he became a famous artist and was considered the leading portrait painter of his generation. He exhibited multiple times at the Salon, created approximately 900 oil paintings and more than 2,000 watercolors. He died in London in 1925 at the age of 69.

But what about Ferrara?

She was born in 1861 in Anacapri, to a working-class family. Before Sargent, she had modeled for other 19th-century artists, including Charles Sprague Pearce, Frank Hyde, and George Randolph Barse.

When Sargent left Capri, Ferrara stayed on the island and continued modeling for artists. In 1891, she married American painter George Randolph Barse and moved to the United States. In 1934, Ferrara died of pneumonia. Four years after her death, Barse committed suicide.

This is all the information I was able to collate from multiple online sources - more than I expected, if I’m being honest. Muses don’t always have a story, and it feels important to share Ferrara’s.

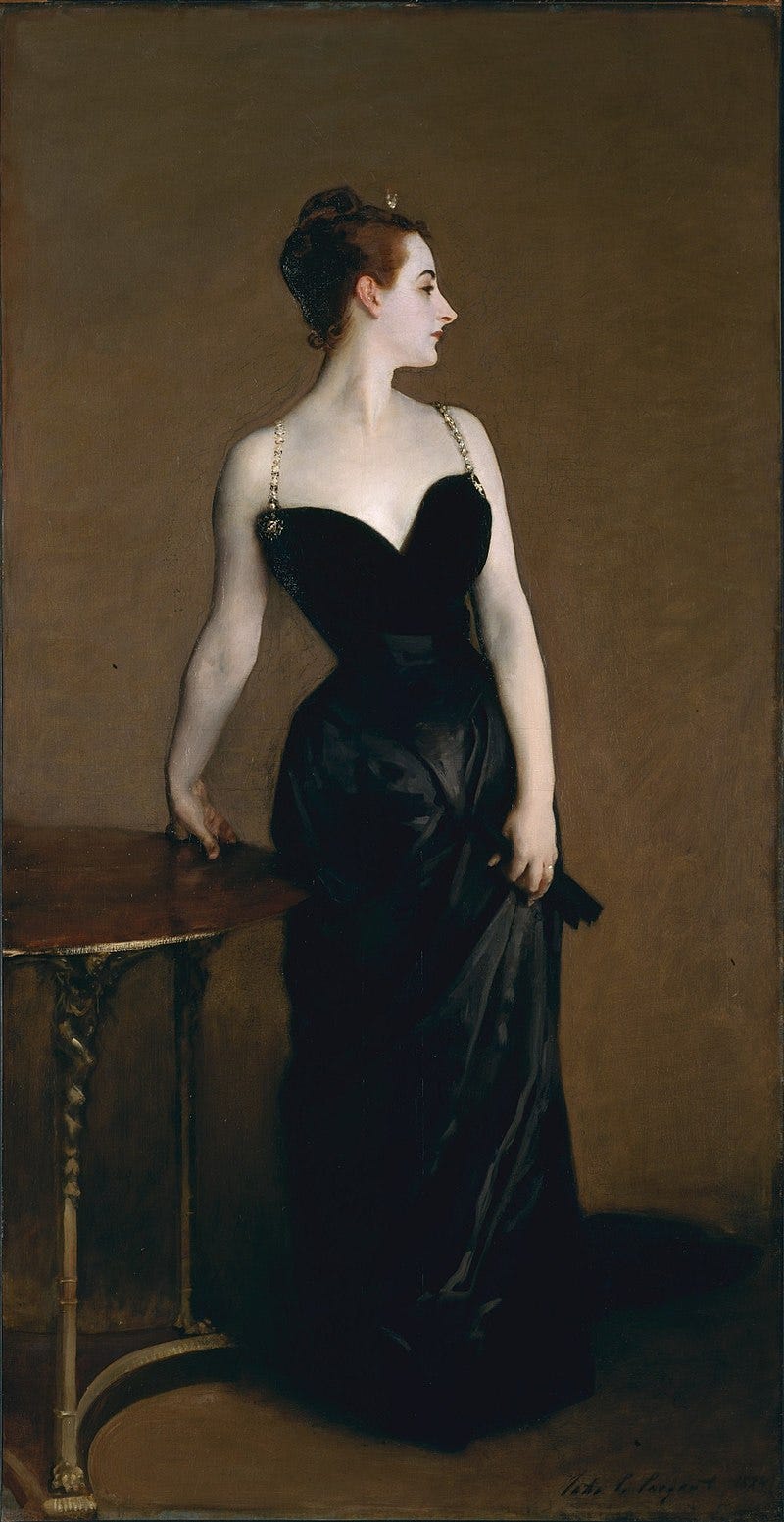

2. Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau

I took AP art history in high school and remember my teacher telling us about the scandalous Madame X - her long black gown with its famously delicate straps. I remember how thrilling it was to learn that Sargent originally painted one of them slipping off her shoulder. How transgressive! At 16, I’d let the strap of my tank tops slide down my arm, trying out what I thought was my own rebellious, sultry look. When it happens by chance today, I still feel some type of way. Some things never change, I think, as I stand in front of Sargent’s painting at the exhibition. I think about how an exposed shoulder is rarely accidental.

So who is Madame X?

Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau was born in New Orleans in 1859. At 19, she married Pierre Gautreau, who was 40, and moved to Paris. There, she quickly became a socialite, one of the city’s most talked-about people.

She is often described as a “professional beauty,” a label used for women whose social currency was their appearance and allure.

Gautreau moved through parties and exhibitions as if it were all part of a performance. She emphasized her pale skin with lavender-colored powder, applied blush to her ears, and dark pigment to her eyebrows. She dyed her hair with henna and wore form-fitting dresses to enhance her hourglass figure. All these elements made her look uncanny, a woman made of marble. A wall text in the exhibition tells me that Marie Bashkirtseff, a young painter in Paris, wrote in her diary that the effect of all that makeup was "horrible in daylight. . . . But at night she is truly very beautiful."

Maybe Gautreau was made for candlelight.

Society saw her as a deviant. At a time when women were expected to be modest, decorous, and private, Gautreau did the opposite - she made herself highly visible.

To no one’s surprise, then, when Sargent met her in Paris, he immediately sought to paint her. Around the room where Madame X hangs, I am surrounded by a plentitude of preparatory sketches of Gautreau (he made over 30, the most he’s ever done for a painting). Sargent was captivated by Gautreau’s striking side profile - the sharp angle of her nose, the bold sweep of her thick eyebrows, and the assertive thrust of her chin. She is almost always shown in strict profile, emphasizing her classical beauty.

Madame X debuted at the Paris Salon in 1884 under the name Madame *** to protect Gautreau’s anonymity. Sargent and Gautreau loved the painting, but they had severely miscalculated what the public’s reaction was going to be.

Everyone hated it. Her dress strap, initially painted falling down, was indecent. Her skin, pale and painted, was unnatural. Her pose was haughty. Her expression was defiant. Viewers rejected her refusal to play the demure beauty.

While the painting captured everything Gautreau had already projected in public, it was something altogether different to see those qualities fixed permanently on canvas and displayed so boldly. That a woman could step beyond the private sphere and deliberately claim the power of the public gaze was threatening, and Gautreau’s hyper-visibility subverted the foundations of what a respectable woman was supposed to be.

Gautreau is a modern icon precisely because she dared to become art itself, a living statue whose brazen self-display continues to unnerve and captivate viewers.

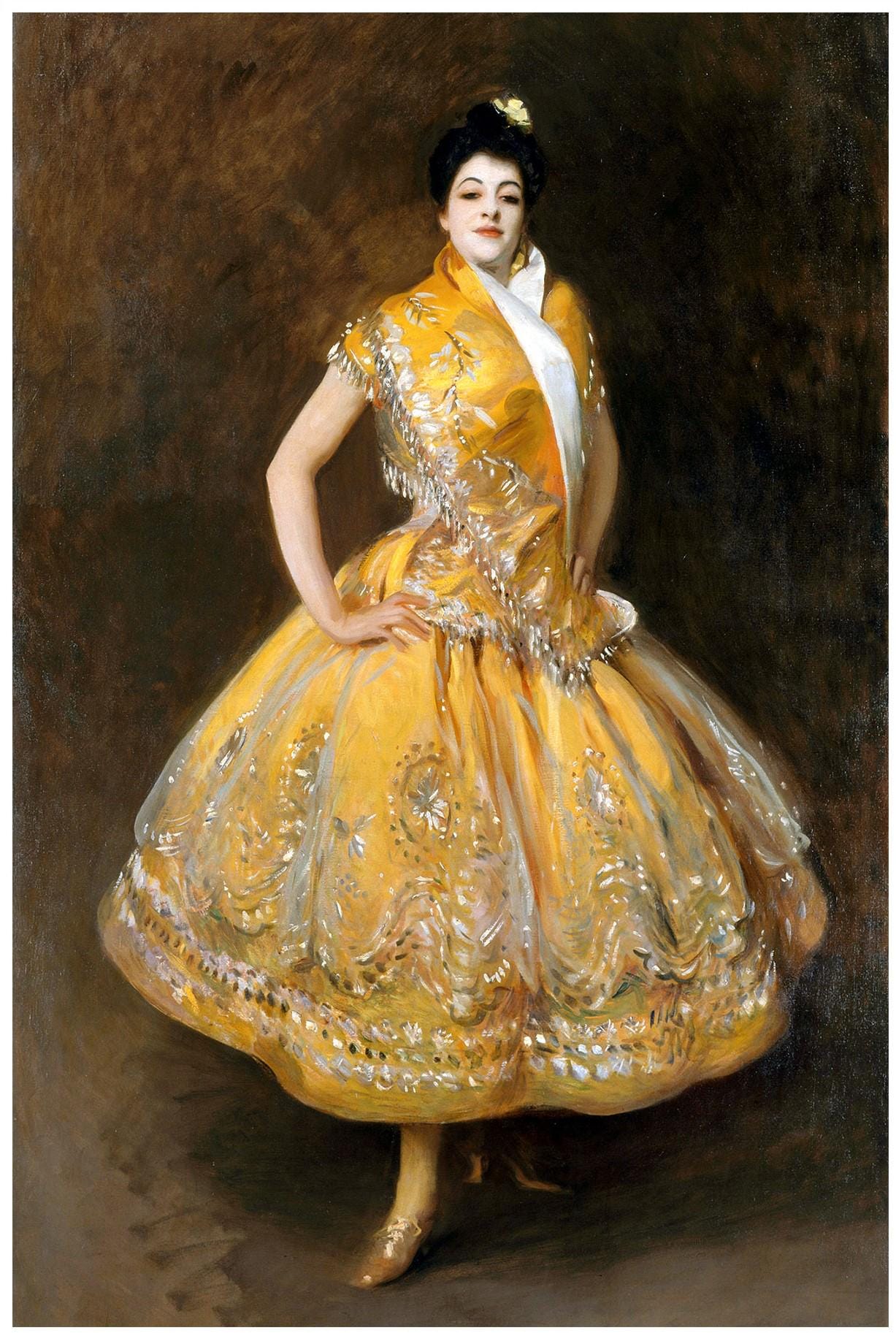

3. Carmen Dauset Moreno

The art of dance is a common theme of Sargent’s oeuvre. He painted dancers in The Spanish Dance (1879-1882), flamenco dancers in El Jaleo (1882), and tarantella dancers in Capri Girl on a Rooftop (1878). The dancer’s movements, the flow of their dress, their abandon while they perform - all beautifully rendered on canvas.

At the very end of the exhibition space, I find one last dancer. She is not performing but standing tall. Her expression is proud, her chin raised, her hands firmly on her hips, and one foot planted in front of the other as if to claim her ground. Her name is Carmen Dauset Moreno, but the world knows her as her stage name (and title of this painting) - La Carmencita.

Her gaze gives me pause. Direct and confident, I almost blush as I meet her eyes. Her hair is pulled back in a chignon to fully reveal her face - pasty white skin, red lips, and dark eyebrows. I spend so much time captivated by her features that I almost forget to take in the voluminous golden-yellow dress with silver embellishments she’s wearing. As much as it fills the canvas, it isn’t the first thing I notice.

According to the wall text, Sargent met Moreno in 1889 at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. There’s not much information on Moreno herself, but the text does share that La Carmencita was purchased by the French state for the Musée du Luxembourg - acquisition that helped establish Sargent as one of the masters of his time.

Born in Spain in 1868, Moreno started dancing at a very young age and toured Spain, Paris, and Portugal. In Paris, she performed at the Nouveau Cirque, and shortly after was signed by a US management company. She debuted in NYC in 1889 and later, under new management, performed regularly at a music hall on 23rd Street in Manhattan. She returned to Europe in 1894 and died at the young age of 42 in 1910.

She was a woman who made her talent her legacy - an artist in her own right, celebrated and respected for her craft.

In a magazine clipping, I found an interview from her run at the Boston Theatre where Moreno talks about her work:

"My dances? Yes, I compose them all myself and they are very fatiguing as you can see. The Spanish dance has much movement of the body and this last, "El Bolero" is very tiring. l rest very quickly however, for I have danced so much I am used to it, but I feel the fatigue a great deal for a few minutes.

I have a new dance, which I give tomorrow night. It is called "La Petinera," and it was very popular in New York. It is full of life and motion."

In the book Carmencita, the Pearl of Seville (1890) by James Ramirez - a novel written explicitly to promote Carmencita’s dancing - she is praised for her beauty:

“a face whose complexion seems made out of magnolia and rose leaves; her eyes are dark as midnight with the most brilliant of starry gleams shooting through them, or as one of her numerous admirers has more originally described them, 'like deep, dark pools whose flashing ripples when put in motion make the head swim’; her forehead is low like the antique foreheads, but full and perfect in form and united with a nose as finely chiseled as a cameo, and her lips are like pouting rosebuds and full of unbridled voluptuousness that discloses, when she smiles, two rows of the most even and pearly teeth, while her luxuriant hair that frames all is as black as the raven's wing.''

But also her talent:

"My rhetoric fails me, for no words of mine can describe the grace and witcheries of that, and I can only say what I have heard artists and sculptors declare, that she looks when she glides upon the stage like some goddess who has come down from her pedestal, and expresses in her every movement the incarnation of the poetry of motion, the rhythm of music, and the beauty of plastic and painted art."

La Carmencita is also film history. Moreno, in fact, is the first woman to appear in a modern motion picture for commercial purposes, and the first woman to appear in a motion picture within the US. She stars in the homonymous silent film La Carmencita, filmed by William Heise between March 10 and 16, 1894, at Thomas Edison’s pioneering Black Maria studio.

La Carmencita, is also credited as the very first title listed on IMDb (historically known as Internet Movie Database) - with the index code tt0000001.

Below is the film and the dance’s description from Ramirez’s novel:

She began her dance that could only be described as a complete set of movements made up of crouchings and springs, serpentine curves, contortions, gyrations, evolutions, convolutions, whirlings and twirlings, so that the dancer appeared in the height of its delirium on the point of going to pieces (…) and after each voluptuous and sinuous movement she turned a dazzling but enigmatical smile to the audience (…) It was such a dance with its audacious whirl and swirl, swaying backward and forward and sidewise, such as might have been danced by the bacchantes who knew how to madden the revellers of old (…) Her constant kaleidoscopic changing of attitudes showed forth the grace of the brilliant quivering of the humming bird, the blowing of flowers in the wind, the rippling of the waves of the sea, the shooting and sparkling of a flame of fire, the waving of banners on the breeze, and depicted every phase of the poetry of motion.

4. Honorable mentions

Hope you enjoyed reading as much as I enjoyed visiting the exhibition! Itching to get back to the city for my next museum trip.

Thanks for reading La Miccia. You can find me on Instagram and Tiktok. If you want to work together, email info.heritagin@gmail.com