The Pope loves AI

On the Vatican's new digital model, the cultural sector's tech transformation, and what that means for authenticity

In this article:

St Peter’s Basilica digital experience

The difference between digitization and digitalization

Authenticity as an individual feeling rather than a universal, objective concept

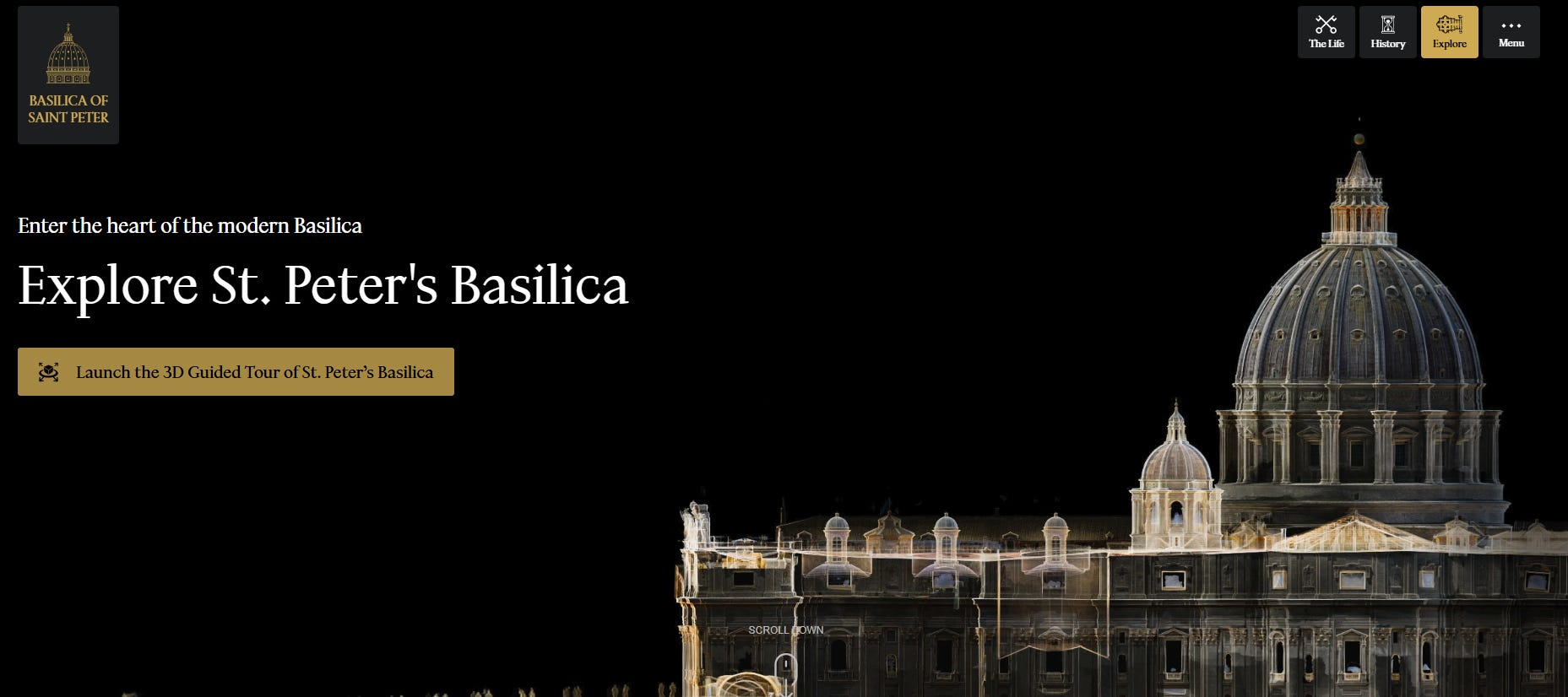

This week, the Vatican, together with Microsoft and Iconem - a French startup specializing in the digitization of cultural sites - unveiled an AI-powered digital replica of St Peter's basilica in Rome.

Microsoft and Iconem used AI and 400,000 high-resolution images from drones, cameras, and lasers to create the ‘digital twin’, a digital model which offers online visitors access to every nook and cranny of the Basilica, without the hours of queuing. The project is being launched in anticipation of the 2025 Jubilee - when 30 million pilgrims are expected - and it intends to improve visitor flow and identify conservation needs.

Microsoft’s Brad Smith describes the project as one of the most advanced of its kind and lauded its accessibility, "we are taking St. Peter's not just to the world but to a new generation of people, in a language that is more accessible for the times we live in". Pope Francis is also stoked, “this house of prayer for all peoples has been entrusted to us by those who have preceded us in faith and apostolic ministry, therefore, it is a gift and a task to care for it, in both a spiritual and material sense, even through the latest technologies”.

You can experience it yourself here. The image quality is spectacular, I have to say.

On top of the creation of the ‘digital twin’ and the digital exhibition on the website, all the data collected for the project is being leveraged to develop a Minecraft Education module and two ticketed immersive exhibits ahead of the Jubilee.

Here’s why this digital model is interesting:

It reveals detailed, never-before-seen views of St. Peter’s Basilica

It’s a powerful tool for conservationists and archivists, as it can help monitor the Basilica’s condition and maintain historical records

The collaboration is just generally cool and unique, merging one of the world’s oldest institutions with cutting-edge tech

It democratizes knowledge by being accessible to anyone with an internet connection

The Vatican’s digital twin of St. Peter’s Basilica also highlights a broader trend: cultural institutions worldwide are embracing digital advancements to remain relevant and engage visitors.

AI is everywhere.

In 2021, the Louvre in Paris launched an immersive VR experience centered on Leonardo Da Vinci and the Mona Lisa, while the British Museum in London introduced augmented reality tours for kids. Across the Atlantic, Rio de Janeiro’s Museu do Amanhã uses IRIS+, a chatbot that provides real time sign language interpretation, enhancing accessibility for hearing-impaired visitors. The list goes on.

Cultural institutions and heritage sites are undergoing a digital transformation

This pervasive tech driven change is marked by two main components: digitization and digitalization.

Digitization refers to the process of using technology and AI to boost visitor engagement. This includes things like immersive experiences, virtual and augmented reality, personalized tours and tailored content created with AI, interactive exhibits, etc. While digitalization refers to the conversion of physical catalogs to digital storage. For example museums digitalizing their collections, or libraries digitalizing their physical archives.

Visitor expectations are evolving, with a growing demand for technologically enhanced experiences. The trend toward digitization and immersive exhibits reflects this shift, as more visitors want entertainment with their education - or ‘edutainment’. As a result, cultural institutions and heritage sites face mounting pressure to adapt to an increasingly digital society and they are renegotiating their traditional roles as cultural guides and drivers of economic regeneration.

While digitization is driven by the necessity to keep the visitor engaged, digitalization can happen for different reasons. The virtual conservation of physical artifacts eases their natural degradation, like in the Vatican’s case for example. The ‘digital twin’ that resulted from the project showed degraded areas in need of reparation, and it predicted “specific areas of future deterioration”, commented Dr. Noha Saleeb, Associate Professor at Middlesex University. On top of that, digitalization allows anyone, from anywhere, to access the institution’s contents once they are online. Ideally, this accessibility should enable diverse audiences to engage with heritage in new, interactive ways.

AI keeps authenticity a debated topic

It is no secret that AI and it’s adaptations are controversial. From algorithmic biases, to historical inaccuracies, to job displacements, new technologies come with their fair share of issues. At the core of concerns about implementing AI in the cultural sector lies the question of authenticity - not just in relation to objects and artifacts but also in the experience of engaging with heritage sites.

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines authenticity as "the quality of being real or true," while Merriam-Webster calls it "not false or imitation: real, actual."1

Both definitions are vague and, mostly, open to interpretation. What does it mean for something to be real? Or true?

In the context of cultural experiences (which include visiting heritage sites like St. Peter’s Basilica), the question of authenticity becomes even trickier. A common concern is that digital reproductions, however accessible, don’t offer the same experience as engaging with the heritage in person. For example, if heritage sites and cultural spaces are important for collective memory-making (aka being in a space with others experiencing the same thing), then the Basilica’s digital twin does not offer an authentic experience. Clicking through a website does not compare to being there in person.

This raises the question of whether physical presence is essential to authenticity and, if so, what elements define an authentic experience. Even when we travel to a historical site like the Vatican, the experience is mediated by modern influences: exit signs, electric lighting, and other tourists wearing flip flops, so how authentic is it, really?

It’s easy to go down the rabbit hole of trying to define what a real, true, authentic experience is. And in most cases, the desire for authenticity is really a search for historical accuracy - is the site/artifact original to its time period, or is it a replica? And if it is a replica, am I, the visitor, informed that it’s a facsimile?

This distinction between authenticity and historical accuracy is crucial. In the case of the Vatican's digital twin, while it may not provide an authentic experience in the traditional sense, it is by all means historically accurate - a faithful representation.

Authenticity, then, is not defined by being in situ (in the original place) nor is it compromised by engaging with a replica - provided that visitors are aware it’s not the original.

So what happens when we aren’t aware that something is a replica?

In Wearing, Gillian (2018), artist Gillian Wearing uses AI technology to deepfake her own likeness onto actors’ faces. By doing this, she challenges the very idea of authenticity in art.

The viewer can’t distinguish between the real Wearing and deepfake version and if the artist hadn’t revealed that a deepfake is included, we wouldn’t even have known. Both versions look and sound like the real, authentic Wearing. There is no perceptible difference between them.

Wearing’s work raises multiple questions:

In a world where AI and digital tools are intrinsic to art, culture, and life itself, does it matter if we can’t distinguish an original from a replica?

If an artwork or experience feels authentic to the viewer, even when it’s digitally altered or created through AI, can it still be considered authentic?

If the experience feels authentic to the person engaging with it, can we truly claim it isn’t?

Perhaps authenticity is about how the person engaging with the heritage feels. If someone feels a genuine connection to a place, object, or experience, then it becomes authentic to them. This subjective view of authenticity is increasingly relevant in a world where digitalization is reshaping how we engage with cultural heritage.

The Vatican's adoption of AI technologies highlights the inevitability of these tools in the cultural sector. As more institutions integrate AI, the concept of authenticity will continue to shift and cultural experiences won’t be defined by originality or physical proximity. Ultimately, the boundaries between physical and digital worlds are blurred, and these experiences are increasingly shaped by individual perception and rather than universal constructs. What we’re witnessing is a shift from traditional collective meaning-making, to individualized, tailor-made experiences.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also like:

The UNESCO World Heritage Operation Guidelines also proposes a definition of authenticity, but it’s mostly directed at UNESCO world heritage sites. I think it’s a bit too narrow for the purposes of this article, feel free to disagree with me in the comments.